Inside the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet

Words By Charlie Dunne & Photography by Perth Ophaswongse

One of the highlights of my time in watches was visiting the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet - the new AP Museum. To visit the Musée Atelier Audemars Piguet required taking a train from Geneva into the isolated, mythical Vallée de Joux.

Upon arrival, I walked the hills behind the building and admired the new spiral pavilion that was designed by Bjarke Ingels of BIG. As cliché as it sounds, time seemed to move very slowly in the village of Le Brassus. Whether walking down the streets or in the fields, there was a feeling of tranquility, devoid of the distractions back in the city. While I loved my experience in Geneva the prior week visiting the Patek Philippe Museum, traveling out to the remote area that truly embodies the heart of watchmaking was ultimately the highlight of my trip to Switzerland. Below is a selection of photos captured by my colleague and friend Perth Ophaswongse (better known on Instagram as @edinburghtimepieces) along with my thoughts on some of Audemars Piguet’s most incredible vintage timepieces.

Upon entering the showroom, we were met with interactive displays on escapements and complications, which set the bar on what we were about to encounter. One particular timepiece that I had been eager to see was a vintage digital-wristwatch with reeded sides. Audemars Piguet created this example circa 1928 and it is the same watch featured within HODINKEE's “Historical Perspectives Inside The Archives Of Audemars Piguet” video and corresponding article. These are remarkable timepieces incorporate what appear to be the same jump hour and digital calibres from Louis-Elissée Piguet of the prestigious Piguet family, known for being the complications specialists from the Vallée de Joux.

Similar examples have surfaced over the years, one at Important Watches, Wristwatches and Clocks by Sotheby’s New York (Feb, 1993) that was sold through Gübelin in 1930. Another had appeared at auction that was retailed at Beyer in 1931. Archived photos show a timepiece with the same case, but instead bearing analog expression in the book ‘Audemars Piguet: Masterpieces of Classical Watchmaking’ by Gisbert Brunner, Christian Pfeiffer-Belli, and Martin K. Wehrli. However, it is the digital models I find to be the most interesting. One can only imagine the reaction this would evoke when shown on the wrist nearly a century ago.

While AP is renowned for its complications, I find many their vintage time-only timepieces to be breathtaking. This is certainly the case for the pocket watch sold by Lucerne-based retailer Gübelin. Many of Audemars Piguet's most spectacular timepieces were sold by Gübelin, so to see this pocket watch in the collection was quite special. The case resembles many of the “knife edge” models that LeCoultre and Cartier were known for during the preceding decades (and advertised as “The Thinnest Watch In The World”). This double-signed dial is the epitome of restrained beauty, making no attempts to capture attention from others. Instead, it displays a very sober design with a mere elongated numeral at 12 o’clock and subtle nod to the longtime friend of the manufacturer. In all likelihood, the interior movement is elaborately finished whereas the exterior case features a tranquil concentric brushing.

Although I could not locate the pocket watch in any Gübelin advertisements, I was able to discover it within one by Birmingham-based retailer W.A. Perry & Co. from 1958 and a 1962 Audemars Piguet featuring a variety of stylish timepieces. Quickly skimming the Europa Star database, I also came across one more from the mid-1950s.

The Museum was home to several pocket watches decorated with miniature portraits. For works like the 19th century timepiece above, few artisans were capable of this type of work, and it is extremely uncommon to see a portrait created in this size today. On one end, I’m very fond of witnessing vintage and antique timepieces out in the wild. On the other, I believe timepieces like the present example are ideal for museums (preferably those dedicated specifically to watchmaking).

Collecting vintage Audemars Piguet is a bit more complex compared to the other haute-horology houses. While there are certainly financial barriers of entry (such as the hyper-competitive Royal Oak A-Series market), finding a well preserved watch from AP is an obstacle in itself. However, there is one area of vintage Audemars Piguet that still remains accessible for the humble collector’s budget: 31mm time-only dress watches.

A fantastic sight was the reference 5043 featuring the ultra-thin 9’’ movement calibre 2003. These cases were made by Eggly & Cie, the casemaker bearing the Geneva key symbol containing 23. It is paired on a beautiful mesh bracelet that was flush with the case. This was the first time I had seen a bracelet added to the 31mm dress watch, as they are predominantly worn on leather (seen in both the Allemann and Türler advertisements below). Due to the short lugs, I am inclined to believe the bracelet was original with the model.

Audemars Piguet advertisement featuring the reference 5043. Image credit: Europa Star (ASIA | 1953 | ISSUE #19)

For collectors who may need a bit of help in admiring these watches, I would stress it features an under-the-radar movement. The calibre 2003 is somewhat of an iconic movement that is rarely discussed, although in AP literature the calibre is championed for being highly important for its era.

"...movement manufacturers were challenged to develop flat calibers. The first step was a modification of the old, time-tested calibers, cutting off their corners more or less sharply. This made them much more suited to the aforementioned cases that were flattened to the sides. But the next step had to be making the movements themselves flatter. An outstanding achievement was scored by the firm of Audemars Piguet, which developed their 9-ligne Caliber 2003 (diameter 20mm, height 1.64mm) for mass production in 1946. For many years, it would remain the flattest available hand-wound movement. Because of its low height, it opened all sorts of possibilities to the case makers."

Advertisement featuring the vintage Audemars Piguet reference 5043 retailed by Allemann. Image credit: hifi-archiv.info

A Multi-Geometric Audemars Piguet model 5179 from circa 1960. The white gold case was made by Eggly & Cie and houses the calibre 2001. Like the calibre 2003, the 2001 was a reliable movement that AP used for decades.

Of course, the design of the Royal Oak makes up most of the conversation when AP is brought up. However, the design highlights for me were certainly the time-only model 5179 and the asymetrical model 5182 dating to the early 1960s. I can only imagine a handful of these were produced, so just being in the presence of these was a thrill.

Perhaps one of the most incredible asymmetrical vintage watches, and a collector’s dream: A vintage Audemars Piguet model 5182 (circa 1962).

Audemars Piguet may have more of a reputation associated with their calendar timepieces, yet many of the exciting complicated wristwatches within the Museum are chronographs. The above timepiece is a monopoussoir (single-button) chronograph. According to ‘Audemars Piguet 20th Century Complicated Wristwatches’, the calibre 11GCCV movement inside dates to circa 1930, and the watch eventually sold in 1948 to the retailer Roehrich in New York. One can presume the movement was originally intended for a pocket watch, but the movement sat patiently waiting for an order to be placed, and eventually was placed in a wristwatch. This is an extremely rare timepiece that is the only one known of 3 documented examples. No model or reference number is designated to this timepiece, however the casemaker (again, Eggy & Cie) and diameter of 31mm are mentioned within the manufacturer’s Archives.

My first encounter with the Audemars Piguet Museum was during Watches & Wonders in Miami in 2019. The manufacturer was the only brand that showcased a vintage collection in what they described as “a traveling Museum”. When I came come across one specific two-register chronograph in a corner of the showcase, my jaw was left wide open. The watch I fell in love with that day was the Audemars Piguet “Cambrée” retailed by Astrua. The Heritage Department cites only one mention of a timepiece like this, potentially making it a unique piece. The movement dates to circa 1933 and it was ordered by Astrua in 1936. As I stood inches in front of it, I couldn’t help but think how reencountering the watch over two years later, and halfway across the world, felt incredibly special.

At one point in the guided tour, I noticed that many timepieces on view were paired on vintage (or vintage inspired) leather straps. This was in stark contrast those on display at the Patek Philippe Museum that can be almost exclusively seen on black patent alligator straps. That look appears too formal in my view, and I find it to limit the personality of the timepieces. In the case of the two register monopoussoir chronograph, or the “Cambrée” retailed by Astrua, the watches appear to capture the era better on brown and tan straps that could pass as leathers dating to the 1940s. Perhaps this detail is more discernible to a vintage watch enthusiast, but it certainly added a feeling of going back in time to see these timepieces.

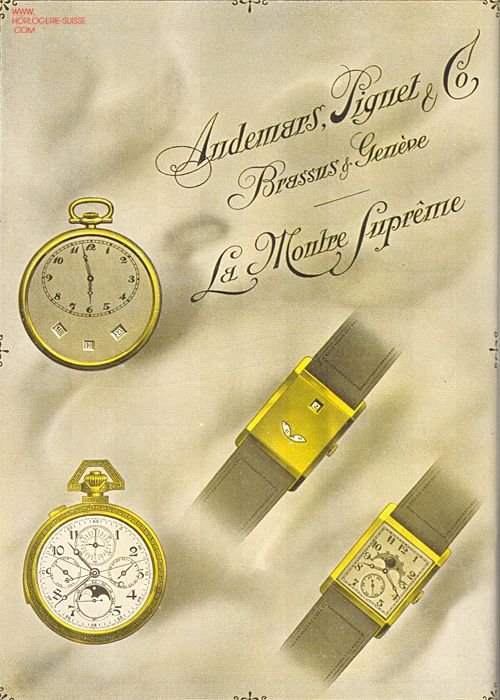

When I asked Ms. De Vleeschauwer about any personal favorite timepieces on view, she cited a pocket watch with applied Breguet numerals, and three calendar apertures positioned on the bottom hemisphere of the dial. This example is just one of many complicated pocket watches which solidified the manufacturers’ reputation amongst its peers in the 20th century. While AP advertisements from this era are few and far between, the design is in fact featured alongside a split-second, minute-repeating perpetual calendar that incorporates a Greek key motif (or meander) around the bezel.

One of the several important perpetual calendar wristwatches on view in the museum is none other than the Model 5516 retailed by Tiffany & Co. The Model 5516 is one of the many iconic timepieces produced by AP in that it was the first serially produced perpetual calendar wristwatch incorporating a leap year indicator. Notably on this example, the 48-months indication is not present as seen in earlier examples. This particular example is one of the six known examples with moon phase above 6:00 (of nine total - the first three had moon phase by 12:00), and the only example of the three 5516 examples in the AP collection to bear a double-signed dial. The movement was manufactured in 1957, and the timepiece eventually sold in 1969. Eric Wind of Wind Vintage stated, “The Audemars Piguet reference, or Model, 5516 is one of my favorite watches ever. Adding a leap year indication to a wristwatch was an extremely important horological accomplishment that made a perpetual calendar wristwatch more functional. Helping discover a previously unknown reference 5516 from the family of the original owner in Florida - an example that was unpolished and in spectacular condition, was one of my highlights at Christie’s and it would be a dream of mine to own that watch in the future.” You can see photos of that example here on HODINKEE and the link to the Christie’s listing here. It sold for $545,000 back in December 2015, but is certainly worth significantly more today.

A unique minute repeating Audemars Piguet wristwatch from 1932 w/ platinum case and dial. The movement was made in 1929 and the watch later sold through Güebelin in 1934 to an American client by the name of W. Talmann.

At only 31mm large, the Eggly & Cie made minute repeating wristwatch by Audemars Piguet was larger than life. While it could easily be overlooked amongst its siblings in the collection, this is one of the most important timepieces in the curation. It is in fact the same exact watch featured in the AP Complicated Wristwatches book with the movement number 38518.

This watch was sold in Tokyo of 1989 by Habsburg & Feldman (Antiquorum). Luckily, this important wristwatch eventually found its way into the collection of Audemars Piguet and can now be witnessed by those who make their pilgrimage out to Le Brassus.

Afterwards, we were able to go the top story of the museum where vintage timepieces are are serviced. I think it is worth emphasizing that Audemars Piguet appears to be one of the manufacturers that is highly conscious of their past productions. De Vleeschauwer highlighted that AP was aware of the position of vintage collectors and reiterated the manufacturer’s approach to changing as little as possible. Obviously many timepieces will be functionally compromised decades after leaving the Vallée, and in these situations the watchmaker’s employed at the factory are capable of recreating necessary components by hand if not available.

Easily one of the most remarkable timepieces we encountered was the Audemars Piguet coin watch. It is no secret that I love these creations, and my interest drove me to write the article ‘An Introduction To Coin Watches: Where craftsmanship meets currency’ on Rescapement. This particular example appears to be an early example of a coin watch, with its beautifully painted numerals and Breguet hands. It was apparent when I inquired about the coin-form timepiece that the watchmakers also shared enthusiasm for these relics. The interior featured a remarkable engraving of the previous owner’s name “Hugh Brooke”.

Towards the end of the tour before making our way to the restoration department, we approached the The Universelle timepiece. This particular moment was memorable as De Vleeschauwer added a more personal note on the passing of AP watchmaker Angelo Manzoni who helped bring this highly important timepiece back to life. This was not an easy undertaking for the brand. The restoration of this watch, deemed at the time as the most complicated AP timepiece and one of the most complicated watches in the world, was conducted by two of Audemars Piguet’s most important watchmakers, Francisco Passandin and Manzoni. Manzoni was not only an integral member of AP’s restoration department, but it is apparent that he was a beloved colleague and friend to everyone who mentions their relationship with him.

Special thanks to the entire Audemars Piguet team for the wonderful experience in Le Brassus: Laura De Vleeschauwer, Sebastian Vivas, Raphaël Balestra, Michael Friedman, Natacha Roydor, Tijana Joksovic, and Halim El Moghazi. A very special acknowledgment to Perth Ophaswongse of Subdial for his incredible assistance in photography and friendship. Additional thanks to Tony Traina of Hodinkee and Eric Wind of Wind Vintage for their editing and support.