How Rolex Became Rolex: The Oyster Case Story (Part 1)

By Owen Lawton

Eric Wind’s Note: Owen Lawton is an extremely talented scholar of watches and is currently a Master of Engineering Materials Science student at the University of Oxford. He is somewhat unusual in the world of watch writing in that he analyzes watches from more of a technical, patent-oriented point of view rather than one more focused on aesthetics. Owen’s future is extremely bright in the world of watch scholarship and I am extremely excited he is tackling “How Rolex Became Rolex” from a technical point of view in 3 parts, starting with this story of the Rolex Oyster case.

How Rolex Became Rolex: The Oyster Case Story (Part 1)

Three innovations propelled Rolex to become arguably the most famous Swiss watchmaker and one of the most famous luxury brands in the world: the automatic winding rotor (“Perpetual”), the Oyster and Jubilee bracelets, and, arguably the most significant, the “Oyster” water-resistant case. In the eye of the general public, Rolex makes durable high-quality watches. This is largely due to their water-resistant “Oyster” cases.

The story of how Rolex was propelled to its current status starts before its founding in 1905 and centers around the famous English Channel crossing of Mercedes Gleitze in 1927. Hans Wilsdorf’s use of this historic event to market the Oyster catapulted Rolex towards becoming the most recognisable watch brand in the world.

Water-Resistant Watches

Making watches resistant to water was extremely important, as water ingress leads to rust and movement damage, and thus they no longer work as intended. Watches are tools and in the case of expeditions and military combat, not having a working watch could have life-altering implications. Case makers in the 19th Century understood this, and companies worked to develop some of the earliest attempts of water-resistant watches.

1927 advert for the Rolex Oyster. Image credit: Rolex.

Oyster Over The Years

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 3131 circa 1946

Rolex Oyster Air-King reference 4499 circa 1945

Rolex Oyster Perpetual 'Bubbleback' reference 2940 circa 1946

Rolex Oyster Royal reference 6244 circa 1952.

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6298 circa 1953

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6112 with date from circa 1953

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6098 with “honeycomb” and “galaxy” dial circa 1953

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6584 circa early 1950s

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6332 circa 1953

Rolex Oyster reference 6022 circa 1953

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6084 circa 1958

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 6614 circa 1957

Rolex Oyster reference 6426 circa 1958

Rolex “Boy Size” Oyster Perpetual reference 6548 circa 1958

Rolex Oyster reference 6082 circa 1960

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 1002 circa early 1965

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 1002 circa 1967

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 1018 circa 1969

Rolex Oyster Perpetual reference 1002 circa 1969

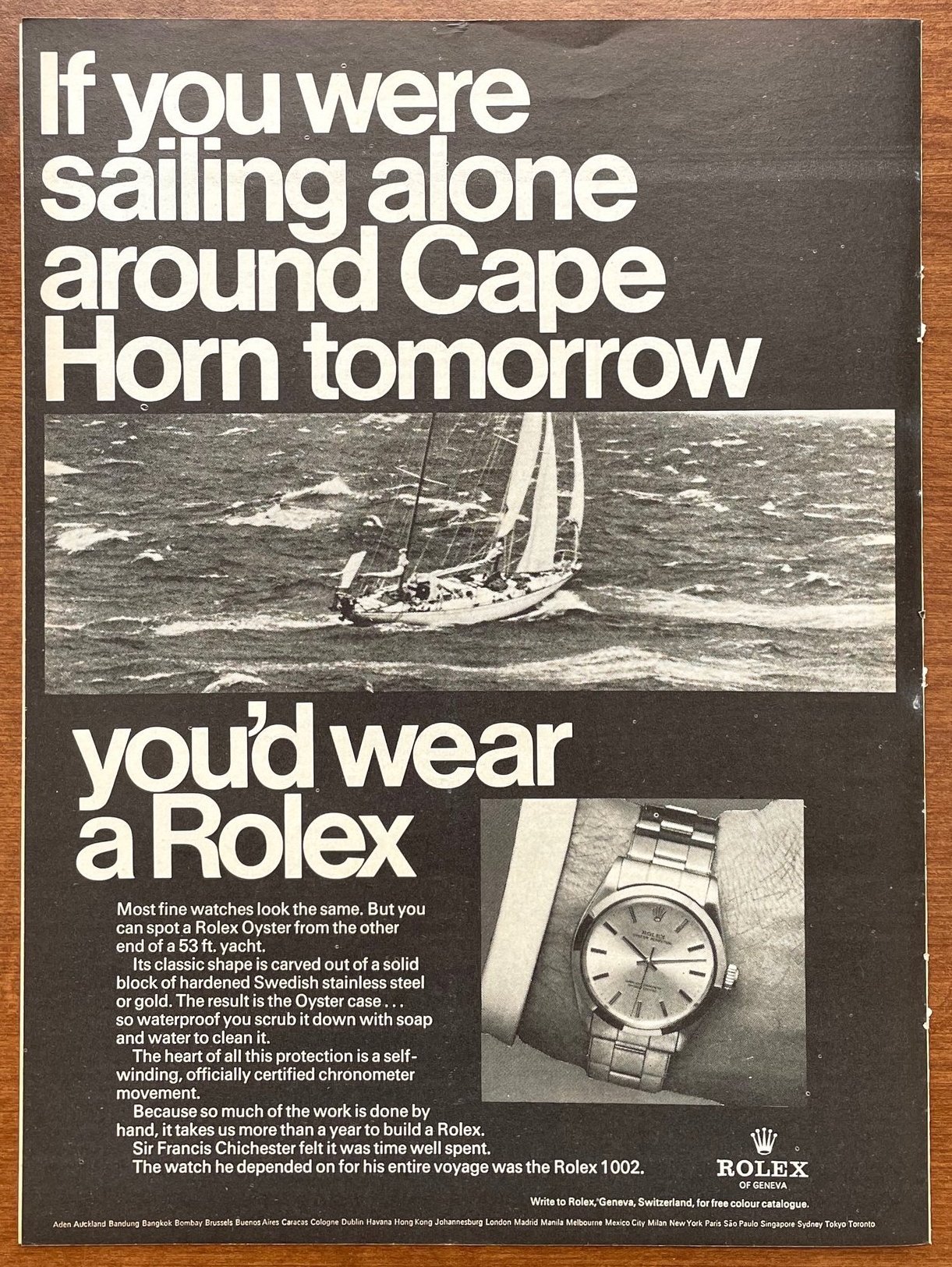

Rolex Oyster Advertisement. Image Credit: Ad Patina

Rolex Oyster Advertisement. Image Credit: Ad Patina

After setting out en masse to create different means for sealing cases, many of these skilled craftsmen found unique solutions, as demonstrated by the patents granted to case makers of the era. Prior to Rolex’s waterproofing methods, the demand for wristwatches had been much lower, but it was the marketing of the Oyster in particular that helped increase demand for this previously niche product.

There are several misconceptions around early water-resistant watches, as well as the patenting surrounding the Oyster case. These range from the belief that the Borgel and Perret-Perregaux patents were used in the Oyster case, through to the aggressive marketing of Mercedes Gleitze’s Channel-crossing Oyster and the assumption that this was the first of the water-resistant Rolex watches.

Rolex and Borgel

Borgel’s patent (CH4001) was ahead of its time in 1881, with wristwatches still being unpopular. It was only during World War I when there became a more practical and popular need to read the time on a wrist that wristwatches started to gain commercial traction. The early Borgel watch case is considered a one-piece case, whereby the movement is mounted to a threaded ring with the bezel and crystal attached. This ring is then screwed into the case.

Image: Diagram featuring in the Borgel patent of the one-piece case credited as the first waterproof wristwatch case (CH4001).

Rolex introduced their first water-resistant watches in 1910/11 using the Borgel one-piece case. David Boettcher of Vintage Watch Straps identifies a Borgel one-piece case marked W&D, the sponsor mark of Wilsdorf & Davis, indicating that this was one of, if not the, first water-resistant Rolex watches

In 1919/20 Rolex began manufacturing watches with the 1903 Borgel three-piece case. The Borgel three-piece case was an improvement on the one-piece and used a case back and bezel with crystal that each screwed into the case, sealing it from water ingress. Boettcher considers this an important step leading towards the Oyster case and identifies a three-piece Borgel case marked with W&D.

Other water-resistant Rolex watches from the 1920s followed, such as the “Hermetic,” which became the Rolex Submarine, but the Borgel three-piece case from 1919/20 formed what would become the Rolex Oyster in the coming years.

The Problem Of The Crown

The greatest challenge facing case makers for waterproofing was ingress around the crown. An example of this is the Perret and Perregaux crown patent (CH114948), which many incorrectly credit with being a part of the Oyster case.

Image: Crown system patented by Perret and Perregaux (CH114948).

It is known Wilsdorf bought the 1925 patent from Perret and Perregaux: however, this patent is not used in the Oyster case as it was flawed. The crown system that Perret and Perregaux developed was reverse threaded and had no clutch, meaning if the watch was fully wound, the crown could not be screwed back into the case in order to seal it.

This isn’t to detract from the significance of the patent. After acquiring the patent on July 24, 1926, Wilsdorf acquired the trademark ‘Oyster’ for Rolex on July 29, 1926. The speed at which Wilsdorf acted shows how he felt he might have been onto a product that he knew would market well and generate sales for what was still a young watch company in Rolex.

Wilsdorf’s Genius

With the belief that a waterproof watch could be a mainstream success, Wilsdorf tasked the case maker C.R. Spillmann & Co SA (a company founded by Charles Rodolphe Spillman) with developing a waterproof watch case. The result was an octagonal case bearing the Oyster name in 1926. This was the case that was around the neck of Gleitze on her channel crossing.

Image: Oyster case patent (CH120851).

There were two key features of the Oyster case that made it waterproof, both protected with patents. The first was the three-piece case where the bezel with crystal and the case back was screwed into the mid-case, sealing the movement from the elements (CH120851). The second was an improved crown system (CH120848) with an internal clutch for allowing the crown to be screwed down onto the case even if the watch was fully wound. Boettcher states: “it was really the screw down crown that was the most significant breakthrough of the Oyster design, which owes nothing to Borgel”.

Image: Patent drawing for the improved crown system for the Oyster case (CH120848).

It should be noted though, that the method for waterproofing the case is identical to the Borgel three-piece case. There was no known collaboration between Borgel and Rolex to produce these cases; however, it is speculated that Rolex was able to acquire the patent for the Oyster case potentially due to the octagonal shape as opposed to round.

Later in 1929, Wilsdorf purchased the rights to a patent owned by The Taubert Company, the then-owner of The Borgel Company. Boettcher wonders whether this could have been compensation for not objecting to the Oyster patent on the basis of prior art as the case was identical, except for the shape, to their three-piece case.

Image: Gleitze during a North Channel attempt. Credit The British Library Newspaper Archives/Gleitze archive.

Then in 1927, Gleitze crossed the English Channel with a Rolex Oyster around her neck, becoming the first British woman to cross the English Channel. This was not her first attempt, nor was it her first successful attempt. In fact, Gleitze successfully crossed the English Channel on her eighth formal attempt. However, it was shrouded in controversy after another British woman claimed to successfully cross days later in a faster time. This was later proven false, yet it undermined Gleitze’s claim. Gleitze was then pressured into a vindication swim in much colder conditions. On this crossing, she wore a Rolex Oyster around her neck. It was engraved on the case back as being the “Companion Oyster” on her “Vindication Channel Swim”.

Auction catalogue image of Gleitze’s Oyster in 2000. Image credit: Christie’s

British swimmer Mercedes Gleitze (1900 - 1979) during her successful attempt to become the first woman to swim the Straits of Gibraltar, 6th April 1928. Image credit: Getty Images.

Image credit: Forbes.

The extent to which Wilsdorf went to market the Rolex Oyster in association with her Channel crossing was probably unprecedented. When thinking of the first people to swim across the English Channel, many think of Gleitze, yet the first person crossed in 1875.

This is not to detract from the achievements of Gleitze. She was a trailblazer in her own right, being the first person to swim the Strait of Gibraltar in 1928 and many other channels in her career. She was also a philanthropist, donating prize money to homeless refugees in Leicester and setting up the charity the Mercedes Gleitze Homes for Destitute Men and Women, which continues to operate today under a slightly different name. These few words cannot do justice to the extent of her achievements and with a film titled Vindication Swim scheduled to be released this year, hopefully, more light can be shed on her feats.

Gleitze set a precedent for the Rolex ambassador. Through to today, the ambassadors Rolex chooses to represent them are at the pinnacle of their field. Whether it is athletes or explorers or musicians they show the peak of human achievement and lead to the association that Rolex is at the top of watchmaking. The Rolex watches they wear can go anywhere and conquer anything in the same way that the Gleitze Oyster was the companion in conquering the English Channel.

The Most Significant Rolex In History

Eric Wind has stated that he believes that the Oyster that accompanied Mercedes Gleitze on her vindication swim is the most significant Rolex in history. It is the watch that propelled Rolex into the public eye and the later success of Rolex could not have happened without it. In a “masterstroke” by Wilsdorf, he set a precedent for the aggressive and successful marketing that Rolex continues to pioneer to this day. Beyond the technical excellence of the company’s Oyster cases, bracelets, and automatic “Perpetual” winding, Rolex would not be Rolex without the prestige of their marketing, sponsorships, and endorsements.

Gleitze’s Oyster watch with its octagonal case made of 9-carat gold and Glasgow import marks for 1926 was last seen at a Christie’s auction on June 20, 2000. Consigned by a descendant of Gleitze, the catalog notes it was displayed at the Rolex 50th Anniversary Reception in Greenwich in September 22, 1976. It sold for £17,038 to a private collector. Surprisingly, Eric Wind understands that it is still in the private collection of the gentleman who purchased it in that auction and remarkably, not owned by Rolex. What it might sell for if it came up for auction is anyone’s guess, but one would expect, perhaps even hope ,that Rolex would attempt to purchase it for their private collection. For without the development of the Rolex Oyster case and Mercedes Gleitze’s Rolex Oyster, Rolex would not have become Rolex.

Endnote: Many of the patents mentioned were filed for in multiple jurisdictions. For clarity, the Perret-Perregaux patent CH114948 is GB260554 in the United Kingdom. The improved crown system CH120848 is GB260554A in the United Kingdom, US1661232A in the United States, and DE443386C in Germany. The octagonal Oyster case CH120851 is GB274789A in the United Kingdom, US1727531A in the United States, and FR638179A in France.

Acknowledgements: I would like to thank David Boettcher of Vintage Watch Straps for the wealth of knowledge he has collected and shared through his website www.vintagewatchstraps.com and for the assistance he has provided.

Owen Lawton is a watch collector, writer and photographer based in the United Kingdom. Lawton is student at Oxford University writing about productivity, watches and Materials Science. You can find his writing on the OxWatch Newsletter owenlawton.substack.com, and follow him on Instagram at @_oxwatch.